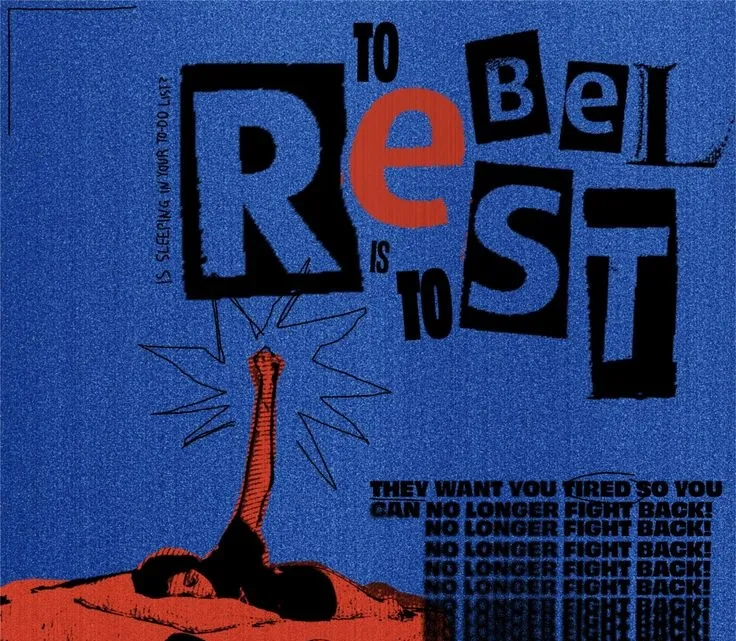

You stay up until 2 am scrolling reels you don’t care about because it feels like rebellion against your should-go-to-bed self, telling yourself “I deserve to relax after this shitty day.” The college kid skips class for months and posts about it like an achievement, a proud transgression. Both of you think you’re being autonomous. You’re not.

This is what I call reactive agency, where you feel agentic because you’re Making Choices™, but all your choices are just responses to external structure rather than internally generated goals. Maybe it feels satisfying because breaking rules give you immediate feedback and clear metrics (did I get caught? did I get away with it?).

The college student is not actually choosing what they want to learn or do. Instead, they’re defining their actions by the breaking of a rule vs. what they actually spent that skipped class time doing instead. The reward is inherent in the rule-breaking.

samantha ponce, 2025

A different way to put it is that people tend to act as if there is an external authority involved, substituting rebellion against imaginary authorities for actual agency because it’s easier to define yourself in opposition than to figure out what you actually want.

In addition, this puts you at the whims of those with the dark art of frame control. When you justify mistakes with “others did it too,” you’re implicitly accepting that the authority’s judgment system is the correct one - you’re just arguing for equal treatment within it.

This is also why agency is actually really quite hard. People will cite being willing to break rules as agency: to be willing to sneak into an event, wearing hoodies to meetings, having contrarian takes (”react is bad actually” LOL, s/o my apple coworker justin), ignoring social norms…

people use rule-breaking as a cheap substitute for the harder work of figuring out their own values. it’s much easier to know what you’re against than what you’re for.[1]

Another pitfall is when people outsource their moral reasoning to imaginary scorekeepers (that external authority) instead of engaging with the actual situation in front of them.

Such as, when realizing you made a mistake, you justify it with, “well to be fair, xyz other person did that too a while ago.” This sort of reasoning only works when your world is just, say, between you, your sibling, and your mom, but not in the real world.

This shows up everywhere:

in activism: instead of asking "does this protest/campaign/policy actually reduce the specific harm i care about?", people ask "does this align with the approved activist playbook?"… like environmental groups focusing on individual carbon footprint messaging bc that’s the established approach even when research shows systemic changes have way more impact.

in relationships: keeping mental scorecards; “you didn’t text me back for 3 hours yesterday so i’m not responding to you for 3 hours today” which treats the relationship like there’s some fairness referee

sidenote

there’s this blog post by Supernuclear about running a group house that I really like and live by: Fairness is overrated and bragging is underrated. Essentially, fairness-based systems accidentally train people to optimize for doing the minimum rather than maximizing good outcomes.[2]

in (especially self-led) work: “i put in my hours” vs “did i actually contribute anything useful?” people optimize for looking productive to the imaginary boss-in-the-sky rather than creating value.[3]

in personal growth: forcing yourself through books you hate because “reading is good for you” instead of finding what actually expands your thinking / interests you.

your parents/teachers are no longer watching you anymore!

whoever gets to set up the scorekeeper system has enormous power. once people accept “fairness” or “precedent” as the metric, they stop questioning whether that’s the right metric.[4]

—

This also generalizes in some other interesting ways.

responsibility diffusion: people use external authorities (real or imaginary) to avoid owning outcomes. “i was just following orders/rules/precedent” lets you feel moral without bearing the psychological cost of choice. milgram experiments, bureaucratic evil, etc.

social proof: external authorities let you coordinate with others without having to argue about values. “we both follow rule X” is easier than "let me convince you my judgment is sound."’

—

There’s an interesting phenomenon that, when I hear someone talk about hating their job or disliking their situation and I, or someone else, mentions they can try to change it, they respond with “not everyone has the privilege to do this…” or something along that vein.[5] But, (if) you’re in your early-ish 20s and don’t have dependents, you actually can change many things about your life! It doesn’t have to be immediate, and it doesn’t have to be sudden, but the rhetoric today limits people too much.[6]

“I can handle way more than I can handle” - AWARDS SEASON, bon iver[7]

When someone says “not everyone has the privilege to quit their job,” they’re often really saying “if i admitted i could quit, i’d have to figure out what i actually want to do instead, and that’s terrifying.”[8]

Yes, structural constraints are real, but people also use them as cover for choice-avoidance. It’s definitely just easier to blame capitalism than to admit you don’t know what career would make you happy. or it’s easier to cite student loans than to run the actual numbers on whether you could swing a lower-paying job you’d prefer.

I think this might stem from this weird thing where acknowledging agency feels like victim-blaming yourself. like if you admit you have options, you’re somehow invalidating real difficulties, but this creates a trap where legitimate constraints get mixed up with learned helplessness. And, what is particularly cruel is that this framework often hurts the people it’s supposed to protect the most, who actually have much more mobility than they think, but discourse tells them they’re powerless![9]

—

Once you see this pattern, you’ll start noticing it everywhere. The hardest part isn’t noticing when you’re being reactive, it’s actually sitting with the silence after you stop doing that and then having to figure out what you actually want.

personally, i have no clue yet. :)

—

Find this post on substack (if you’d like to comment or subscribe).

Also… me when I say I’m “losing the idgaf war.” It’s definitely good to just care, to show your friends you actually like them, to keep asking to hang out and not overthink the “how relationships should work” rules. ↩

Here’s another good post by them: Meet Cheryl, your coliving nemesis. ↩

I do agree there’s much more nuance here; there’s a legitimate argument that it can be “just a job” when you do actually have a boss… but let’s imagine you’re trying to get somewhere with the work, either climbing that specific ladder or it’s your company. ↩

Schools/jobs accidentally train this and social media rewards this behavior, with how platforms reward hot takes and dunks, which are just reactive positioning. It’s so much easier to build an audience by being anti-something than by creating something. ↩

"Now, yes, this can be true! There are some legitimate things that prevent you from making big drastic changes in your life, and this advice definitely is not encompassing all the nuance, but those things are actually pretty few and far in-between. ↩

One alternate example is location: you should not be tied to a city just because all your friends live there. If you think you’d thrive more / have more opportunities somewhere else, you can always build new communities and meet people. ↩

Listen to this song—this lyric is beautiful in context, and then read this post: Bon Iver is Searching for the Truth (brought me to tears). I think realizing we’re actually capable of so much is amazing, and a lot of modern culture maybe makes us feel bad about this? It’s bad to be egotistical, but you’re allowed to be confident and the culture in many places today encourage you to seem humble and downplay yourself… but we start to believe the narratives we tell and therefore lose our confidence. ↩

To be clear here, to reference my advice post, most of the stuff I’m talking about here are things I consistently try to tell myself, so there is no clear solution nor am I claiming that the solution is easy. I also don’t know what my goals should be! ↩

I’ve seen this quote somewhere I forgot, but it is along the lines of you should not think statistics applies to you. Obviously that’s delusional, but looking at the numbers of how many people have failed doesn’t acknowledge that perhaps you’re actually the exception. Or… you’ve gotta believe you are. ↩